If a person without a mind is a mere chaos, without senses he is a ghost.

– Jack Lindsay, ‘The Individual in Art’

The Spasmodics: the conflict in English poets in the years 1825 – 1860 is an unpublished manuscript by Jack Lindsay, held in the National Library of Australia as part of the Jack Lindsay Special Collection (literary archive). Lindsay had been interested in the poetry of the Spasmodics since the 1950s but his only publication about the group is an essay about poet, Ebenezer Jones that he contributed to a festschrift for his friend, historian A.L. Morton, Rebels and Their Causes (1978). Lindsay identifies Jones as a symbolist poet, though he goes on to discuss Jones as part of the Spasmodic group, identifying the characteristics of their work.

For anyone who does not know of the Spasmodics – they are now an obscure literary phenomenon – there has been some recent interest in the group, with an issue of Victorian Poetry (Vol. 42, No. 4 (2004)) devoted to their work and, even more recently, the publication of Lori A. Paige’s comprehensive study, The Spasmodic Poets: Appraising a Controversial School of Victorian Literature (2022). I first encountered the Spasmodics in the late 1970s, during conversations with Jack Lindsay when he was particularly interested in poets who were directly politically-engaged (e.g. the Chartist poets) and/or who addressed politics via its effect on individual being (e.g. the Spasmodics). For many nineteenth-century (and later) readers the intense emotionalism and sensory excess of the Spasmodics was the result of poor schooling, lack of decent restraint, or a clumsy attempt to emulate the Romantics; Lindsay’s perspective was very different. His notion of human being as fundamentally interconnected – with each other, other beings, and within their own being – led him to identify the Spasmodics as a disruptive, alternative poetic voice, articulating experiences and realities that are missing from mainstream Victorian art – the voices of the poor, disenfranchised, alienated.

The Spasmodics: a contemporary overview

Most current scholars offer a similar interpretation of the Spasmodics’ work. Kirstie Blair (2006) identifies the Spasmodics as not a movement so much as a group of writers who shared interests, philosophy, aesthetics, and class affiliation.

The ‘spasmodic school’ consisted of a loosely affiliated group of poets, largely from working-class or lower middle-class dissenting backgrounds, who were linked by critics because of their penchant for lengthy subepic poems, often featuring a tormented poet-hero and with a focus on unusual imagery, extremes of emotion, insanity, violence, and sexual desire. (p.180)

They were mainly active from the 1830s to the 1850s, with the first major Spasmodic work usually identified as Philip James Bailey’s Festus (1839), a version of the Faust legend, and Tennyson’s Maud (1855) and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh (1856) included among the last examples of Spasmodic writing (Laporte and Rudy 2004, pp. 421-27). The sensory intensity of their work influenced many of the writers who followed them, Florence Boos (2004) citing their impact on the early poetry of William Morris and Kirstie Blair (2006) their influence on Swinburne.

The evocation of heightened sensation in Spasmodic verse meant it walked a fine line between pathos and bathos. For example, Sydney Dobell’s Balder (1854) is described by Blair as‘his well known spasmodic epic in which the hero meditates at length on poetry, Nature, and man, before apparently murdering his child (and thus driving his wife mad) in an attempt to experience the ultimate in sensation.’ (2006, pp. 182-3). This is a shocking story and perhaps not surprisingly was met with outrage by many readers of that time. To locate Dobell’s views Rudy cites the study by Scottish philosopher Alexander Bain, The Senses and the Intellect (1855), which argued that intellectual thought was directly related to bodily experience. Bain envisaged thought as ‘currents’ moving through the brain, prompted by sensory encounters, rather than the more popular notion of the brain as a depository in which knowledge is stored. For Rudy, Dobell’s interest in Bain’s work demonstrates a number of points about his work and his aesthetic, which are also apparent in the work of his colleagues. It showed that the Spasmodic poets, like the Romantics before them, were not opposed to science, but embraced its new ways of thinking about human being and knowing. And it demonstrated their determination to utilise these insights creatively in their own work, rejecting the notion of a mind/body dualism for one of embodied being, in which mind and body are fundamentally interrelated. Rudy concludes that it is the very fact that Dobell’s work was based in the most contemporary scientific and philosophical research that made his work seem so dangerous to his critics: ‘the mutterings of a madman might more easily have been dismissed’ (p. 466).

That dismissal was often derived from and expressed as class prejudice. Despite being mostly working-class or lower middle-class and sometimes politically and socially activist (e.g. Ebenezer Jones and Sydney Dobell were Chartists), these poets had the effrontery to act outside the usual restrictions of their class; they presumed to write. Boos (2004) quotes Richard Cronin’s view that the damaging attack on their work by Aytoun ‘was motivated by the belief that Gilfillan, Smith and Dobell were ill-educated and presumptuous interlopers into cultural precincts that ought to be reserved to their social superiors.’ (p. 556) Recent studies of their work affirm the judgment that class discrimination underlay many negative responses to their work (Harrison 2004; Tucker 2004; Blair 2006). Boos concludes her study with a condemnation of the class prejudice that has afflicted British literary judgment:

‘More disspiriting were the enduring triumphs of the iron laws of class and education that Aytoun exploited. No acknowledged “major” poet of Victorian Britain came from working- or lower middle-class origins, and none of the “spasmodists” is likely to gain more than token entry into any twenty-first-century anthologies. Even here, however, Dobell, Smith and the others might have found a measure of vindication in the vast palette of subsequent generations’ preoccupations with despair, recovery, aberrance, marginality, and self-examination—a palette they helped, in the face of withering critical abuse, to configure.’ (p. 579)

The work of the Spasmodics sliced through the mannered civility of bourgeois society to reveal the alienation and pain at its heart, suppressed and ignored by the middle classes and, if articulated by the working classes, dismissed as vulgar or amateurish.

Jack Lindsay and the Spasmodics

In his study of George Meredith (1956) Lindsay discussed the influence on his subject of a group of post-Romantic poets that he identified first by the title, the New Poets and later as the Spasmodics. Lindsay described their work as combining the influence of Byron, Shelley and Keats into a new synthesis ‘which clarified the place and destiny of man on earth, of poetry in society – specifically in the society of expanding capitalist industrialism.’ (p. 44). The group included R.H. Horne, whose work Lindsay credited with demonstrating to Meredith ‘the concrete link between social struggle … and poetic activity’ (p. 43) and whose epic poem, Orion (1854) Lindsay described as attempting to ‘deepen the consciousness of the rebellious energies expressed in the Romantic Movement, so that they may adequately grapple with the social situation of the post-Romantic world.’ (pp. 43-4). For Lindsay Orion was ‘the key-work of the New Poetry, the post-Romantic poetry of the period 1825-55 – a position that it shared with the feverish Festus of [Philip James] Bailey, in which a sense of immense new possibilities in human life wrestles with a sense of doom and disaster.’ (p. 44)

Lindsay’s interest in Spasmodic poetry was piqued by its unabashed sensuousness and emotionalism combined with philosophical or political contemplation. For Lindsay, the political role and power of art lies in not only its direct engagement with social issues but also its ability to bridge between the senses, the emotions and the intellect of the reader. In so doing, he argued, the arts appeal to the individual as an interconnected being, not simply a disembodied mind. The arts can, therefore, be restorative by bringing back together, reintegrating, the alienated individual who lives in a society that artificially separates mind and body. They can be revealing, showing the devastating effect on the individual of beliefs and practices that fragment the wholeness of being, destroying individual integrity. The arts can also be regenerative, demonstrating that human activity involves the whole (sensing, feeling, thinking) individual. And they can be revolutionary, overturning naturalised assumptions about the nature of being that can make possible new ways of being, knowing and acting, which have the potential to transform our being in and acting on the world.

This activist understanding of art was central to Lindsay’s Marxism and his work with the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), though Jack and the Party sometimes diverged in their interpretation of Marxist theory. For many mid-twentieth century Marxists the nature of a society was determined primarily by its economic base (e.g. capitalist, communist), supported and reinforced by its social, economic, political and cultural superstructure that reflected the values, beliefs and assumptions of the base. The superstructure included institutions and practices such as religion, the arts, education, law and order, and the parliament, which enact and normalise the principles motivating the base. Lindsay found this base/superstructure model problematic because it relegated the arts to a subservient, essentially conservative role. For Lindsay the power of art is not simply in the story it tells or the image it presents, but in how it engages the individual, enabling them to see and understand their society differently – and so, potentially, to change it.

The Spasmodics were a limit case for bodily engagement. The febrile quality identified by Lindsay in Bailey’s Festus (1839) and in most Spasmodic poetry led him to describe their work as often ‘extremely confused, unstable, hectic and wild’ (pp. 44-5). It was also the reason that they came to be known as the Spasmodics. This label was not complimentary. It was assigned irrevocably to the group by writer and satirist, William Edmonstone Aytoun in an essay for the Blackwoods Edinburgh Magazine published in May 1854, ‘Firmilian: A Tragedy’ by T. Percy Jones, the author’s name apparently a reference to Spasmodic poet Ebenezer Jones. Firmilian was (written and) represented by Aytoun as a verse-drama that featured many of the characteristics of Spasmodic poetry, particularly emotional intensity and sexual candour, expressed through sensational, exuberant and uncontrolled imagery. It is also breathtakingly awful to read – execrable story, execrable characters, though conventional (non-Spasmodic) poetics that exacerbates, by contrast, the awfulness of the story and the characters. He then severely criticises its [i.e. his] excesses, concluding: ‘They are simply writing nonsense-verses; but they contrive, by blazing away whole rounds of metaphor, to mask their absolute poverty of thought, and to convey the impression that there must be something stupendous under so heavy a canopy of smoke.’ (p. 551) Aytoun’s satire effectively ruined the reputation of the ‘Spasmodics’ and they faded into literary obscurity.

Having re-discovered the group during the research for his book on Meredith Lindsay gives a very different reading of their work from that of Aytoun writing that, despite its flaws and inconsistencies:

‘… it did continually make important advances and showed, at least in flashes, a deep penetration into what was happening to people, the shattering pangs and the great possibilities of delight and brotherhood in the new developments. The confusions all converge on the question as to what kind of struggle, what kind of personal and social development, can overcome the pang and make the possibilities come true.’ (1956, p. 45)

For Lindsay the work of the Spasmodics articulated the individual and societal consequences of rapid social change linked with a transformative technology that destroyed older economic, social and political formations, and so familiar ways of being, knowing and acting. Not all these changes were bad; however, they were confronting and sometimes devastating for individuals and whole communities whose traditional ways of living and working were transformed or eliminated.

For Lindsay the major problem with the Spasmodics was that they had no consistent social or political theory that they could use to analyse and critique the changes that were transforming their society and the lives and being of its citizens. Even so, he argued in his essay on the work of Ebenezer Jones (1978), ‘they reveal richly the nature of the crisis they confront and the new possibilities opening up in culture, in human relationships; at their core is a quest for the new kind of union that will overcome the evil effects of the dehumanising forces at work throughout society.’ (p. 152) As with Dickens (Lindsay, 1950), their social activism lay with this ability to dramatise the individual and social consequences of living through the ascent of industrial capitalism. However, where Dickens was a brilliant populist engaging millions with his eccentric characters, the Spasmodics were punks, trashing the establishment with overblown lyrics, less than perfect literary technicality, and a wild energy. Perhaps not surprisingly Lindsay found them fascinating and set out to revive their literary reputation. In a footnote in his book about Meredith, he writes that he is preparing an extended study of the group: ‘That book, to be entitled The Spasmodics, I am at work on.’ (p. 45).

In the 1950s, however, the times were against Lindsay’s completion of this project. He had fallen out of favour with the Communist Party because of his views of art and society, particularly as he presented them in Marxism and Contemporary Science (1949). Cold War anti-Communism had already seen him banned from a job he badly needed at the BBC, when an employment offer was withdrawn after intervention by the Security Service (1949). Publishers were dropping known Communists from their author lists and Lindsay had a depressing disagreement with friend and fellow-writer, Edith Sitwell over his proposal to include Spasmodic writer, Ebenezer Jones in his study of British poetry, The Starfish Road (unpublished). As Lindsay explained in his book Meetings with Poets (1968), his intention was to use Jones as an honourable failure as activist-artist, but Sitwell could only view Jones’s work with unalloyed contempt: ‘she roundly trounced him as jejune and platitudinous’ (p.158). As a result, Lindsay also abandoned that manuscript. On top of all the professional and political concerns of the 1950s Lindsay’s much-loved partner, Ann Davies was diagnosed with cancer in 1951. After several years of remedial treatments Ann died in 1954, leaving Lindsay bereft. He completed his book on Meredith but left unfinished and unpublished his study of the Spasmodics.

Ebenezer Jones: a Spasmodic case study

One chapter of this unpublished book was later repurposed for the A.L. Morton festschrift as ‘Ebenezer Jones, 1820–1860 – an English Symbolist’. The text analysis in the chapter focuses on Jones’s work but Lindsay consistently situates the work as Spasmodic poetry, which enables the essay to serve as an introduction to his understanding of Spasmodic writing.

Lindsay introduces Jones’s writing through the words of Dante Gabriel Rossetti in Notes & Queries Volume 41 (1870):

“I met him only once in my life, I believe in 1848, at which time he was about thirty, and would hardly talk on any subject but Chartism. His poems had been published some five years before my meeting him, and are full of vivid disorderly power. I was little more than a lad at the time I first chanced on them, but they struck me greatly, though I was not blind to their glaring defects and even to the ludicrous side of their wilful ‘newness’; attempting, as they do, to deal recklessly with those almost inaccessible combinations in nature and feeling which only intense and oft-renewed effort may perhaps at last approach. For all this, these Studies should be, and one day will be, disinterred from the heaps of verse deservedly buried. Some years after meeting Jones, I was pleased to hear the great poet Robert Browning speak in warm terms of the merit of his work.” (quoted, p. 154)

The collection to which Rossetti refers is Studies of Sensation and Event (1843), Jones’s first published work. Though it was received well by some, most reviews were negative, and the disheartened Jones abandoned hopes of further publication. In 1879, an expanded edition was published posthumously, prompted by the praise from Rossetti, with an added section, ‘Studies of Resemblance and Consent’ containing poems Jones had intended for a following book.

Jones was also a political thinker, publishing his own analysis of the reasons for the injustice he saw around him in The Land Monopoly, the Suffering and Demoralisation caused by it; and the Justice and Expedience of its Abolition (1849). Lindsay writes: ‘The wage-system he denounces as essentially evil; it demoralises the entire people, and is a form of slavery. But society conspires to conceal this deep truth.’ (p. 154) An essential element of this conspiracy is the absolute demoralisation of the working class: ‘The final horror comes when efforts are made to turn the suffering working class ‘contented with their inferiority’. Baseness can sink no lower.’ (p. 155) For Lindsay, Jones’s analysis of the effect of industrial capitalism on individuals is impressive, but his remedy – the redistribution of land – is less so:

‘As a political thinker he is then only an advanced radical attacking the landed interest; but his moral and social analysis is primarily concerned with the essentially dehumanising nature of the capitalist wage-relation, anticipates attitudes of Ruskin and Morris, and is in the key of what his contemporary Marx was thinking about the alienations of class-society.’ (p. 156)

In other words, as a political thinker, Jones is most effective as a poet.

Lindsay begins by specifying three key elements in Jones’s work:

‘(a) the strong sensuous pictorial effect, which clearly had much effect on Rossetti and played its part in bringing about the key-ideas of Pre-Raphaelitism, (b) the strange or bizarre situation, image, event, which dominates in each poem …, (c) the dialectical interrelation of ideas and emotions, which has affinities with Blake’s method and leads on to a doctrine of symbolic correspondences linking Jones with the French symbolistes, with Baudelaire and Rimbaud.’ (p. 159)

He then demonstrates these elements in a selection of Jones’s poetry,in the process answering many objections to the volatility and febrility of Spasmodic verse. Lindsay does not attempt to mitigate the strange and unruly elements in Spasmodic poetry but rather provides them with context and meaning. The Spasmodics painted vivid and bizarre images and orchestrated shocking and confronting events because that was how people were experiencing the social, moral, intellectual and technological changes of the early nineteenth-century. Not literally, but as radical, existential challenges to their understanding of the social, moral and political order that disrupted their fundamental sense of self. Furthermore, in their flouting of poetic and literary conventions, the Spasmodics were not simply revealing their lack of formal education but were consciously disrupting the familiar meanings associated with those conventions. Among the conventions used irregularly in Spasmodic verse were metre and rhythm.

Jason R. Ruby (2004) wrote of Spasmodic poet, Sydney Dobell’s poetics: ‘Rhythm for Dobell expresses metonymically the physiological conditions of the human body – its pulses either harmonize with or strain against the throbbing of our physical beings – and poets communicate most readily through a reader’s sympathetic and unmediated experience of these stressed and unstressed rhythmic impulses.’ (p. 452) Hence, he argues: ‘if Spasmodic poetry threatens Victorian cultural values by unseating conventional notions of gender, sexuality, class, nationality, and religion, Spasmodic poetics—and especially Dobell’s notion of rhythm—threatens Victorian culture by promulgating these unconventional values, by offering a vehicle for the wide-spread dispersal of the eccentric.’ (p. 452). Ruby contrasts this with the response of Aytoun for whom ‘metrical regularity enforces cultural stability as much as rhythmic spasms encourage much that is “wrong” with the times (which for Aytoun included new reform measures and the granting of rights to women).’ (p. 452)

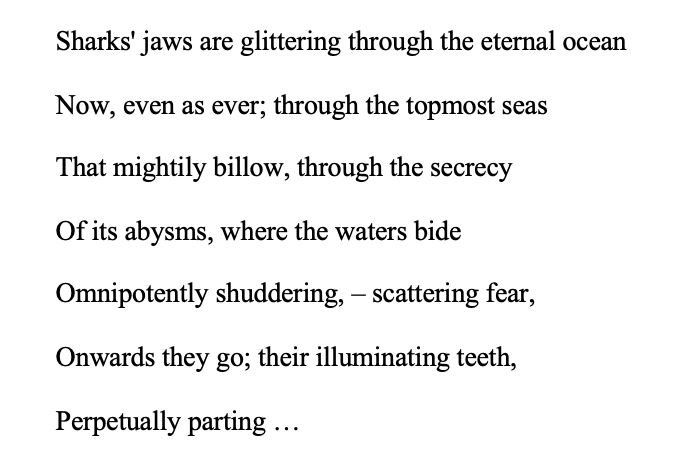

This Spasmodic disruption is exemplified in the opening lines of Ebenezer Jones’s ‘Ways of Regard’ (1879) which present not only a disturbing image of what Lindsay describes as the ‘ravening divisive forces’ (p. 168) of his time, but mirrors their effect on individual being through his use of irregular rhythm and caesura (quoted, pp. 167-8):

Not only would Jones’s readers viscerally experience the fear of a powerful, silent, stalking predator, they would have been in little doubt who were the potential victims in this scenario. There are few such striking images of the rising industrial middle class and the impact of their economic and political practices on early nineteenth-century English society.

The other characteristic of Jones’s work that Lindsay discusses is his interrelation of ideas and emotions. As Rudy notes in his study, this interest in the interconnection of mind and body was prompted by new physiological studies in the nineteenth-century such as Bain’s The Senses and the Intellect (1855): ‘In Bain’s model, the human body becomes a living organism that derives knowledge through subjective, physiological experience, rather than an objective container into which knowledge from the surrounding world is “stored.”’ (p. 455). Rudy describes Dobell’s 1857 lecture on the ‘Nature of Poetry’ as arguing that: ‘It is in one’s “material flesh and blood” that the reader will properly understand the Spasmodic poem, as the brain intuitively converts rhythmic impulses into knowledge, “ideas and feelings.” It is through the spasmodic reaction of the human body to rhythm that the poetry will “live.”’ (p. 454) Certainly, Lindsay’s analysis of the poetry does not disagree, however it goes a step further by introducing a dialectical and self-reflexive element to the reader’s engagement.

For Lindsay, the Spasmodics’ disruptive poetics enabled readers to see and understand differently not only their society, but also themselves. They could read their own bodily responses as symptomatic of the being and consciousness created by their society and its institutions, not as individual moral failings, as Victorian bourgeois notions of self-help claimed. They could also explore ways of changing both society and their own sense of self, thereby rejecting the powerlessness that came with alienation. They could be not just eccentrics, but revolutionaries.

THE SPASMODICS: THE UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT

When Edith Sitwell failed to understand Lindsay’s argument about the worth and importance of Ebenezer Jones’s writing (Lindsay 1968, p.158), he gave up the Spasmodic project, leaving behind an almost complete typewritten draft of sixteen chapters bound in a cardboard cereal packet covered in brown paper (Lindsay’s familiar way of conserving manuscripts, drafts and research papers and cuttings). The draft includes a handwritten Title page and Contents pages with chapter numbers that end at page 245, as the starting page of the penultimate chapter. This chapter, ‘Pre-Raphaelites and others’ and the following ‘Conclusion’ are missing from the draft. At the back of the bound draft are research notes and analyses that are not included in the draft, including a study of Tennyson’s The Devil and the Lady, notes about writers J. E. Read, A.J. Symington, Charles Kingsley and John Westland Marston, and about Philip James Bailey’s Festus.

The handwritten title page to the manuscript appears as follows:

The following is the list of chapters that accompanies the bound draft after whichI have added brief summaries of the contents of the chapters:

Chapter Summaries

Introduction: The Nature of the Romantic and the Symbolist Movements

Lindsay summarises the basic elements of the Romantic movement: (i) the poet feels a deepening division in life – inside himself, and between himself and society; (ii) the poet feels with new force the infinite variety and richness of the Earth, and also the destructive forces alienating him from it; (iii) he conceives the city as a prison compared with nature as freedom; (iv) the organic processes of nature in which man is a person are opposed to the mechanistic world of industrial capitalism which conceives man as a thing; (v) his revolt is fundamentally anarchist, an expression of the isolated individual; (vi) the poet is in a constant state of travail as he tries to make sense of his changing world.

Lindsay then details how this Romantic stance is reconfigured in the post-Romantic period: (i) without any possibility of mass opposition the poet’s role is to map the alienation of the individual even more dramatically; (ii) the poet’s engagement with nature must avoid an escapist capitulation to the forces of alienation and instead find new ways to articulate the fundamental union between humanity and nature; (iii) the city is now conceived as a prison and as ‘the battlefield of values’; it now becomes the site of resistance; (iv) the poet can no longer rely on simple oppositions such as organic v. mechanistic and natural v. artificial but needs an understanding of the dialectical interrelationship of all factors – natural and artificial or mechanistic – that constitute their world and their being within that world; (v) the poet will be keenly aware of the bodily experience of alienation but must maintain the positive move towards a just society, ‘a world without exploitation and the reduction of man to a thing’; (vi) the poet’s sensitivity to the individual experience of crisis must now become the ground for a new awareness of shared experience that will be the ground of unified struggles for freedom. For Lindsay these points are realised in Symbolist poetry, which he then compares with Romantic poetry, through analyses of Shelley’s ‘Ode to the West Wind’ and Keats’s ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ (Romantic) and Baudelaire’s ‘Le Squelètte Labourer’ (Symbolist).

1. The Reputations and influences of the Great Romantics

Lindsay considers the effect on the Spasmodics of the ‘Great Romantics’, particularly Wordsworth, Byron, Shelley and Keats. He omits Coleridge on the grounds that he was not yet well-known or influential and identifies the greatest critical thinker of this time as Thomas Carlyle, noting particularly his major influence on Dickens, Ruskin, Meredith and Spasmodic poet, Ebenezer Jones. Lindsay describes the political divergence between Wordsworth and his fellow Romantics, with Wordsworth’s poetry read as purely escapist: ‘The way was open for the final canonisation of Wordsworth, with the disembowelling of his aesthetic, as the saintly mediator between the British bourgeoisie and Nature, with Matthew Arnold as his high priest.’ (p.22) Lindsay argues that Shelley’s work ‘had a much deeper influence’ on the Spasmodics because of the links it maintains to political struggle, despite the attempts of many conservative critics to paint Shelley as a dreamer. And even more influential was Byron, ‘the unveiler of shams … against Wordsworth the sham-veiler’ (p.28). Lindsay identifies Byron as ‘the one poet who had comprehensively grasped and defined the intensest contradictions of his society, of capitalism in its first swelling tide of successful expansion’ (p.36). Those contradictions and the bodily trauma they engender were the subject of Spasmodic verse.

2. The First Stages of the Transition

Lindsay identifies some minor predecessors of the Spasmodics, focussing on Thomas Hood (1799-1845), who is best known for his socially critical poem, ‘Song of the Shirt’ (1843). Lindsay discusses Hood’s macabre work, ‘Mary’s Ghost – A Pathetic Ballad’ (c.1826) which he describes as a ‘mess of horror’ and forerunner to later works such as Baudelaire’s Une Charogne (The Carcase) and Le Squallette Labourer (The Labouring Skeleton). For Lindsay these poems articulate the bodily experience of alienation caused by capitalist work practices, though their authors do not specify the cause of this alienation.

3. The Crisis-Drama: Charnel-Discord and Death-Reconciliation

Lindsay discusses Romantic-era precursors of the Spasmodics, John Wilson (1785-1854) and George Darley (1795-1846), whose work addresses some Romantic (and Spasmodic) concerns: the pestilential city, nature as escape, the alienated individual, the nature of being and consciousness. For Lindsay both writers use phantasmagoric images and scenarios to capture the traumatic experience of industrial Britain but ultimately look for resolution in a transcendental realm, of religion or nature. In Darley’s work, however, Lindsay detects ‘the three forms of relationship, the passive duality of the reflection, the pressure of the unifying depths, the objectification of the conflict in consciousness’ which he identifies as ‘a definite dialectical awareness of the structure of experience’ (p.61). That is, more than a simple opposition of individual and society, or city and nature, Darley’s work depicts the interrelationships of all factors involved in this social transformation and its effect on individual being and consciousness.

4. Paracelsus

Lindsay discusses Browning’s early works, Pauline (1833) and Paracelsus (1835) as Spasmodic texts. In Pauline, Lindsay writes, Browning struggles with his Romantic heritage of rebellion but ultimately succumbs to Victorian beliefs and values; it is ‘a story of how a Shelley became a Victorian with a sense of sin’ (p.64). Browning’s epic poem in five Parts, Paracelsus is similarly compromised for Lindsay in that it aspires to a new kind of human being, by-passing the moral, political and cultural struggles required to engage with the past and so transform human being and consciousness. Paracelsus’ quest for knowledge is thwarted by the same kind of idealist or utopian thinking, which reduces his scientific endeavour to a form of mechanistic thinking, detached from the (moral, political, cultural) world in which it operates. This is mirrored in Paracelsus’ musing on the split between mind and heart, which for Lindsay identifies the fundamental problem of Romantic idealism; that it acknowledges the dualisms – mind/heart, nature/industry, individual/society – that characterise alienated life in industrial Britain but cannot move beyond them. Ultimately, like Pauline, it advises a form of gradualism that Lindsay calls critically the ‘reconciliation-formula’ (p.75).

5. Festus

Lindsay introduces the first major Spasmodic work, Festus (1839) by Philip James Bailey (1816-1902) as a more respectable version of Goethe’s Faust (1790; 1808)and Byron’s Cain (1821), though notes also its engagement with everyday reality and with history – with the embodied experience of people in their everyday lives and its contemporary and historical contexts. He also notes that this impacts on Bailey’s poetics, the work exhibiting an interweave of thought and sensory impression, of ‘inner and outer’ that Lindsay identifies as new. At the same time, Lindsay argues, the politics of the work are consistently reactionary, Bailey resorting to religious and romantic abstractions to resolve the contradictions he detects and dramatizes in everyday life. For Lindsay Bailey is most innovative in his creation of complex sensory imagery that merges colloquial diction and rhythm with Romantic tropes to describe the effect on individual being of the alienating practices and ideology of industrial capitalism.

6. Orion

This chapter introduces the second major Spasmodic poet in the study, Richard Hengist (born Henry) Horne (1802-1884), focussing on his best-known work, Orion (1843). Lindsay begins by discussing an earlier work, The Spirit of Peers and People (1834), a satirical work in which Lindsay detects Horne’s awareness of the effects of alienation and the class-struggle on individual being. Of Orion Lindsay notes that its ‘form, idiom, method’ are basically those of Keats’s The Fall of Hyperion (1818-20) and that the concept is dialectical. In the narrative, Lindsay writes, Orion goes through ‘nodal points of dialectical conflict’ from which he emerges afresh, not simply reconciled to an overwhelming, alienating present. Nevertheless, Lindsay detects vacillation about this political engagement, noting that Horne often falls back into religious abstractions to resolve contradictions between social aspiration and actuality. Similarly, Horne’s notion of the relation between body and spirit moves between the unity favoured by Lindsay and classical notions of harmony or proportion

7. W.H. Smith

Lindsay introduces William Henry Smith (1808-1872) as a minor Spasmodic poet, not the bookseller, who wrote three verse-plays. Each play engages with the Romantic, Byronic notion of the alienated individual which results in either solipsistic introspection or a discouraging sense of the division between heaven and earth, potential harmony and actual division. As well, imagination is viewed as both the creator of illusion and the (critical) function that enables illusions to be identified. Lindsay describes Smith’s third play, Sir William Crichton (1843) as a limit case of Romantic thought in its opposition to the analytic – which it aligns with capitalist money-making – and support for the synthetic – aligned with the drive for human unity that the analytic forces of capitalism destroys. Lindsay observes Smith’s thorough exploration of the nature of society and social movements, though notes he found communism likely to be impractical.

8. Thomas Carlyle

Lindsay identifies Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) as a major social and political influence on the Spasmodics, citing key concepts and ideas such as ‘cash nexus’, which replaces human engagement with cash payment, and ‘Phantasm-Aristocracy’, the contemporary aristocracy who have forgotten their leadership role. Lindsay argues, however, that Carlyle would replace the fallen aristocrat with Captains of Industry and that his solutions all look backwards to an idealised medieval order. He notes that Carlyle’s social and economic analysis anticipates that of Marx, Morris and Ruskin, but also defends capitalist expansion and empire (which Lindsay sees as ‘a forerunner to Nazism’); and that his fear of mass-action prevents him seeing the workers as capable of self-determination. For Lindsay, Carlyle’s arguments were often contradictory or weak, based on his fear of the working classes. He notes that Carlyle turned to the idealism of German Romanticism rather than the rebellious English Romantics for resolution, particularly criticising Byron and Shelley for their support of ‘the people’. In Sartor Resartus (1834), Lindsay argues, Carlyle ‘uses the concept of the unity-of-opposites in an idealist way in order to deny the concrete unity and abstract spirit. And he sets his symbol-universe against the mechanist universe of the capitalists.’ (p. 134) By transposing the revolt against capitalism from the everyday world to a mystical realm, Carlyle provides ‘an idiom for distorting poetic process and reconciling the poet with the existing state.’ (p. 135)

9. Ebenezer Jones

Lindsay introduces the work of Ebenezer Jones (1820-1860) through his Chartist pamphlet, The Land Monopoly, the Suffering and Demoralisation caused by it; and the Justice and Expedience of its Abolition (1849), quoting Jones’s identification of the evil caused by the wage-system of capitalism: “it demoralises the entire people”. For Lindsay Jones’s classification of this evil as not only financial but also psychic or psychological – and cumulatively as social – is fundamental to his poetics. His poetry engages readers through heightened sensory and emotional appeals to make the point that the individual worker experiences the wage-system (and its reduction of employer-employee relations to a cash-nexus) in their whole body (senses, emotions, intellect), not just as an abstract argument. At its worst, capitalism attempts to make the workers “contented with their inferiority” (Jones, quoted by Lindsay). Lindsay demonstrates his analysis with close readings of Jones’s poetry, arguing that his work reveals and deconstructs the process of alienation described in his political pamphlet. Though Lindsay found Jones’s political analysis inadequate – Jones argued for a form of land redistribution, ignoring the problems of industrialisation – he nevertheless identifies him as the poet whose work brings to fruition the arguments of the great Romantics for a practice that includes an understanding of human universality, the dialectics of creative thought, and an analysis of the alienating effects of capitalism and its distortion of human being.

10. Gerald Massey

Gerald Massey (1828-1907) is described by Lindsay as born into extreme poverty and hardship but having an indomitable spirit. When a young man Massey joined the Chartist movement and, despite having little formal education, became editor of the working men’s newspaper, The Spirit Of Freedom. Lindsay praises his revolutionary songs that were based on his own experience as a working-class man but finds his kinship with the Spasmodics in his personal poems such as ‘The Ballad of Babe Christabel’ (1854). Lindsay notes that in Massey’s work there is no conflict between love and politics, the personal and political; rather, Massey believes that all men and women have the right to a full and happy life, which involves both public and private spheres. For Massey, there is no retreat from the political struggle into private emotion as seen in the work of many of his contemporaries; the two exist in a unity. Lindsay adds, however, that Massey’s later poetry lost its critical edge and became more conventional, even at times jingoistic and decadent. However, he concludes that between 1848 and 1854, Massey produced some ‘magnificent’ work.

11. Tennyson as Benison

Lindsay considers works by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) written between 1842 and 1855 – including ‘The Poet’, ‘Confessions of a Second-rate sensitive Mind’, ‘The Deserted House’ and ‘The Two Voices’ – as inspired by the same issues and ideas as the Spasmodics. He notes that Tennyson’s work from this period, though weak, exhibits the acute sensitivity to the social and natural world and accompanying self-reflection that characterises Spasmodic poetry. Lindsay records a contemporary account of these ‘new’ poets as followers of Wordsworth, though he adds Keats and Shelley to Tennyson’s influences. He notes the major appeal of Tennyson’s prosody and refers readers to Spasmodic writer, R.H. Horne’s A New Spirit of the Age (1844), which opens with a chapter on Tennyson. With the publication of In Memoriam (1855), Lindsay writes, Tennyson became ‘the Great Poet of the new bourgeoisie’ (p.174) and a year later was being described as part of the decadent tradition, obsessed with death and decay; a rebel no more.

12. Alexander Smith

Lindsay begins with an account of the early life and influences on working-class Scottish poet and essayist, Alexander Smith (1829-1867), whom he believes to be the successor to Philip James Bailey, author of Festus. Largely self-taught, Smith had some success with his early poetry and so set out to compose a longer work. This became A Life Drama (1852), which Lindsay describes as emulating Festus though replacing transcendental elements with a focus on the growth of the poet: ‘to make of poetry a magnificent force leading men to a full and happy life on earth.’ (p. 181) For Lindsay the poem ‘faces the problem of guilt, refuses otherworldly solutions, and unites its lovers on earth. By confronting and overcoming the fears and guilt … it wipes out the anxieties that wreck Festus and leaves the road open to a fuller advance of poetry as a vanguard force of life’ (p.185), despite Smith’s failure or refusal to see the power and significance of direct political action. Lindsay sees the work in a progression: Bailey’s Festus, Robert Browning’s Paracelsus, R.H. Horne’s Orion, Tennyson’s The Palace of Art, Smith’s A Life Drama. He adds that Smith’s poem was extremely successful though, when he visited London, his supporters were disappointed that he was not the romantic figure they expected. Returning to Scotland, Smith met Spasmodic poet, Sydney Dobell and collaborated with him on a book of poems about the Crimean War, Sonnets on the War (1855). Shortly afterwards, Smith published the collection, City Poems (1857) that described and meditated upon urban life in a way reminiscent of George Meredith’s city poetry.Lindsay notes, however, that Smith’s reputation had been undermined by two scathing reviews published by William Edmondstoune Aytoun in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in March and May 1854 and his later work did not sell well. Smith died prematurely of typhoid fever, aged thirty-seven.

13 John Stanyan Bigg

Lindsay introduces rebellious young story-teller, John Stanyan Bigg (1828-1865) who wrote his first major work, The Sea-King; A metrical romance, in six cantos (1848) at eighteen; and six years later, published the work for which he is principally known, Night and the Soul: A Dramatic Poem (1854). Lindsay notes the fierce critical attack in The Athenaeum on Night and the Soul, identifying the ‘gentlemanly reaction’ as class-based, rejecting the intrusion of working-class life and sensibility into the realm of poetry. He likens this to the scorn heaped on John Keats as ‘vulgar, cockney, radical. Confused, uncontrolled, erratic’ (p.201). Lindsay describes the work as ‘a more extravagant version of [Alexander Smith’s] A Life Drama’, noting the major influence of Smith on Bigg’s work. Lindsay also places Bigg’s work in the context of 19th century Night Poetry, partly because of its imagery of stars in the night sky – a feature targeted by critics of Bigg and the Spasmodics. He notes that when critic, Leigh Hunt pointed out this imagery to Carlyle as exemplifying our ‘elemental union’, Carlyle responded ‘a sad sight’. Lindsay acknowledges Bigg’s attempt to introduce a social justice morality to the work but argues that he ultimately presents love and marriage as an escape from struggle, representing the social as ‘something added superficially, not an integral aspect of the acceptance of earth and the fight for a fuller life.’ (p.215) For Lindsay Bigg’s avoidance of social or political activism confuses his argument and use of imagery and ultimately leads to ‘Tennysonian uniformity’. Nevertheless, Lindsay identifies Night and the Soul as ‘one of the key-expressions of the post-romantic epoch’ (p.216).

14 Dobell and Starkey

Lindsay introduces two poets whom he believes exemplify the failure of the early symbolist impulse in English (Spasmodic) writing: Sydney Dobell (1824-1874) and Digby Bilot Starkey (1806-1876). Dobell grew up in a Christian fundamentalist home with political associations through his maternal grandfather, London Radical leader Samuel Thompson. Lindsay writes that in his first publication The Roman (1850), about the battle for Italian liberation, Dobell conceptualises the process of political change as a battle between ‘Faith and loss of Faith’, avoiding the actual social consequences involved. This abstraction of individual and social transformation marks all of Dobell’s writing including his political works – his sonnets about the Crimean War, co-published with friend, Alexander Smith (1855); the volume, England in Time of War (1856); and the pamphlet, Of parliamentary reform: a letter to a politician (1865) – as well as his infamous Spasmodic work, Balder, Part One (1854). For Lindsay Dobell’s political writing (like that of Alexander Smith) was weakened by his failure to understand or accept any kind of cooperative, working-class political activism, while Balder lost its way in a fog of solipsistic emotion and violence. Lindsay includes politically conservative Irish writer, Starkey largely because his writing was so like that of Dobell that his anonymously published Anastasia (1858) was attacked as an example of the poor writing and self-indulgent metaphysics that for many critics characterised Balder and Spasmodic poetry in general. With this work and the unfinished Balder (Dobell never wrote Part Two) Lindsay concludes: ‘The complex social struggles that underlie Festus, A Life-Drama, and Night [and the Soul], and which to some extent break through, are here finally deoderised into the abstract struggle of theologically-conceived faith and loss of faith … Byron’s challenge to God (to the whole ruling concept of Authority) has been dissipated, and Victorian values of conformity are left supreme.’

15 Break

In this last completed chapter of the draft manuscript (Chapters 16 and 17 in the List of Contents are not in this bound draft) Lindsay summarises his history of and argument about the Spasmodics. He starts by reviewing George Gilfillan’s history and defence of the Spasmodics, including the influence of the Romantics, especially their concern with the complexity and confusion of the age, and the isolation of the poet and retreat into inner worlds. Lindsay then reviews W. E. Aytoun’s critical essay, ‘Firmillian’(1854) which he identifies as an attack on Baileyand his poem, Festus, concluding that the major criticism of the Spasmodics was their focus on ‘the tumults and perplexities of the spirit in their vexed and torn world, without confronting the ground-causes of the trouble’ (p.235). He adds wryly that, if they had been more socially and politically engaged, Aytoun and his fellow critics would have liked them even less. Lindsay condemns the passivity of the Spasmodics in the face of this criticism; they neither defended their work nor tried to present their case more effectively but gave up and died (like Smith and Jones) or joined the enemy (like Massey). He also notes that none of them recognised that the Chartist movement provided the political and social grounding of their work. The outbreak of the Crimean War (1853-1856) confronted the Spasmodics with their failure to influence the hearts and minds of their contemporaries and presented them with the options of becoming more politically engaged, giving up, or joining the patriotic (jingoistic) movement. Those who kept writing became apologists for war. Lindsay concludes with a reading of Tennyson’s ‘Maud: A Monodrama’ (1855): ‘): ‘The distortion of the life-process, of social reality and spiritual truth, could hardly go further. … It [Maud] completes the failure of men like Smith and Massey by twisting their method into a maturely evil definition. Poetry has been made safe for idealism and the bourgeoisie.’ (p. 242)

Conclusion

In these chapters Lindsay celebrates the value of the Spasmodics’ work as a response to the expansion of industrial capitalism in the early nineteenth century and its effect on individuals and communities. At the same time, he does not ignore its problems and failings. Lindsay’s approach is the diametrical opposite from that of W.E. Aytoun, the Spasmodics’ contemporary nemesis. Instead of focussing on the perceived flaws of Spasmodic work and then amplifying and ridiculing them, Lindsay locates the work socially and culturally to reveal its contemporary significance and poetic practice. For Lindsay, in specific ways, the Spasmodic poets were more innovative and perceptive than their more successful, more restrained, and more solidly bourgeois contemporaries such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Robert Browning.

Many Spasmodic poets knew working-class experience first-hand and understood the alienating effects of industrial capitalism on every aspect of individual being and experience, particularly the insecurity and loss of any autonomy or self-direction in the workplace. These are features of the alienation that Lindsay identified with industrial capitalism, and which Carlyle captured with his notion that the relationship between worker and employer had been reduced from a human relationship to a cash-nexus. For Lindsay this was characteristic of a society defined by mechanistic thinking that reduced individuals to things and relationships to (non-contextual) transactions. In Chapter Ten of The Fullness of Life he wrote of early 19th century British society:

Mechanistic quantitative science was exactly paired off with the extension of the cash-nexus; one depended wholly on the other. To get rid of all the thingifications induced by the cash-nexus meant to overthrow the grip of mechanistic thinking in all spheres. The criterion that a thing is true simply because it works and that every exploration or application of the way things work must be carried on merely because it is possible, was the direct result of the elimination of humanity from science, the surrender of humanity to the mechanistic principle. In the early days – right into the 19th century – it was easy to maintain the illusion that thus men were gaining mastery over nature, over things, whereas in fact the things were gaining mastery over men.

From Lindsay’s perspective the Spasmodics were responding to this thingification, which made working-class lives precarious and alienated working-class individuals, at its worst taking from them any sense of self-worth or autonomy. At the same time, it turned the middle-class into the agents of this process, destroying empathy and positioning them to either ignore (or actively not see) the social injustice around them and/or to escape into fantasy worlds of religion, art, jingoistic patriotism, or social Darwinism.

Lindsay also noted the lack of formal education of many Spasmodic poets, which meant their writing was not as measured and restrained as that of their middle-class contemporaries, but also that they were not pressured into conformity with mainstream poetics and the values with which it was associated. As noted earlier, many modern scholars (e.g. Rudy 2004, Boos 2004, Harrison 2004, Tucker 2004, Blair 2006, Paige 2022) have identified in the work of the Spasmodics a sensory poetics that enables them to articulate the individual experience of radical social, economic, cultural and technological change. That experience was not measured and restrained but chaotic, terrifying and sometimes exhilarating, challenging the individual’s fundamental sense of self.

At the end of her study of the Spasmodics (2022) Lori Paige concludes:

Not so long ago, the Spasmodic poets seemed a group without a future. Their “school” was a phantasm created as a tool for ridicule, their poetry dismissed as ephemera bound for well-deserved oblivion. Yet, like the Brontë sisters, the group has undergone a kind of metamorphosis that has restored them to a position of relevance and even respectability. (p. 268)

Jack Lindsay’s study from the 1950s pre-empts many of these recent publications, offering an earlier (mid-1950s) lineage to the appreciation of the Spasmodics’ work. At the same time, it demonstrates Lindsay’s poetics, based in his foundational belief in the unity or interconnectedness of all human being and knowing.

REFERENCES

Aytoun, W.E. ‘Alexander Smith’s Poems’. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 75 Issue 461 (March 1854a): 345–351.

————— ‘Firmillian: A Tragedy’. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 75, Iss. 463, (May 1854b): 533–551.

Bailey, Philip James. Festus: A Poem. Boston: Benjamin B. Mussey, 1845.

Bain, Alexander. The Senses and the Intellect, 3rd. ed. N.Y.: D. Appleton & Co., 1868.

Blair, Kirstie. ‘Swinburne’s Spasms: Poems and Ballads and the “Spasmodic School”’. Yearbook of English Studies, 36.2 (2006), 180–96.

Boos, Florence S. ‘“Spasm” and Class: W. E. Aytoun, George Gilfillan, Sydney Dobell, and Alexander Smith’. Victorian Poetry, Vol. 42, No. 4 (Winter 2004): 553–583.

Browning, Robert. Paracelsus. London: Effingham Wilson, 1835.

Dobell, Sydney. Lecture on the ‘Nature of Poetry’. Delivered in the Queen Street Hall, Edinburgh, April 8, 1857. Accessed on 20/4/2025 at: https://www.lyriktheorie.uniwuppertal.de/lyriktheorie/texte/1857_dobell1.html

Harrison, Antony H. ‘Victorian Culture Wars: Alexander Smith, Arthur Hugh Clough, and Matthew Arnold in 1853.’ Victorian Poetry, Vol. 42, No. 4 (Winter 2004): 509-20.

Horne, R.H. Orion: An Epic Poem in Three Books. London: J. Miller, 1843.

Jones, Ebenezer. Studies of Sensation and Event: Poems. Edited, prefaced and annotated by Richard Heine Shepherd with Memorial Notices of the Author by Sumner Jones and William James Linton. London: Pickering & Co, 1879.

—————. The Land Monopoly, the suffering and demoralisation caused by it; and the justice & expediency of its abolition. London: Chas. Fox, 1849.

Lindsay, Jack. ‘Ebenezer Jones, 1820–1860 – an English Symbolist’. In Rebels and Their Causes: Essays in Honour of A.L. Morton, ed. Maurice Cornforth, 151–75. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1978.

—————. Charles Dickens: a biographical and critical study. London: Andrew Dakers, 1950.

—————. George Meredith: his life and work. London: Bodley Head, 1956.

—————. Marxism and Contemporary Science; or, the fullness of life. London, Dobson, 1949.

—————. Meetings with poets: memories of Dylan Thomas, Edith Sitwell, Louis Aragon, Paul Eluard, Tristan Tzara. London: Muller, 1968.

—————. William Blake: creative will and the poetic image. London: Fanfrolico Press, 1927; rev. ed. 1929.

Paige, Lori A. The Spasmodic Poets: Appraising a Controversial School of Victorian Literature. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2022.

Rossetti, D.G. ‘Ebenezer Jones’. Notes & Queries, Vol. 41 (1870):154. Rossetti Archive. Accessed April 21, 2023. http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/28p-1870.raw.html.

Rudy, Jason R. ‘Rhythmic Intimacy, Spasmodic Epistemology’. Victorian Poetry, Vol. 42, No. 4 (Winter 2004): 451-72.

Tucker, Herbert F. ‘Glandular Omnism and Beyond: The Victorian Spasmodic Epic.’ Victorian Poetry, Vol. 42, No. 4 (Winter 2004): 429-50.